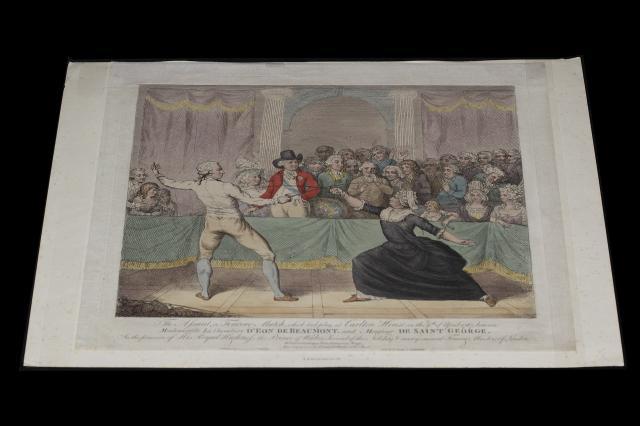

There is an unusual print in the collection at Freemasons' Hall featuring a fencing exhibition staged in front of the Prince of Wales in 1787. One of the participants appears to be a middle-aged woman. It is in fact, the Chevalier D'Eon, one of the most colourful characters in 18th Century Freemasonry. A diplomat, spy, swordsman and Freemason, who lived the first half of their life as a man and the second as a woman.

Diplomatic career

Charles D'Eon de Beaumont was born of minor noble birth in the French town of Tonnerre in 1728. After studying law in Paris, working as an official crown censor, and proving skilful with a sword, they joined the diplomatic service in 1756, just after the outbreak of the Seven Years War. The war involved all of Europe's major powers and D'Eon was sent to Russia and the Court of the Empress Elizabeth, to work as a diplomatic secretary. Unofficially they were also part of an organisation known as the Secret du Roi or King's Secret. Louis XV had started the Secret as a secret alternative to the Foreign Ministry, which was then under the influence of his mistress Madame Pompadour. After some success in negotiating with the Empress, D'Eon returned to France and a commission in the Dragoons in 1761.

The Head of the Secret persuaded Louis XV to send D'Eon as secretary to the French Ambassador, to lead the peace negotiations. At the same time they were to run spies, investigating England's coastal defences. They managed to negotiate the best possible peace deal for France and the King rewarded it, making them a Chevalier of the Order of St. Louis and granting a pension. D’Eon was also made Plenipotentiary Minister of the French Crown – essentially interim Ambassador - running the French Embassy in London until a replacement for out-going Ambassador could be found.

D'Eon made plenty of friends in London, entertaining such luminaries as Horace Walpole and David Hume. The Chevalier also made lasting friendships of the radical politician John Wilkes and of Washington Shirley (Lord Ferres) who would later be Grand Master of England.

Speculation

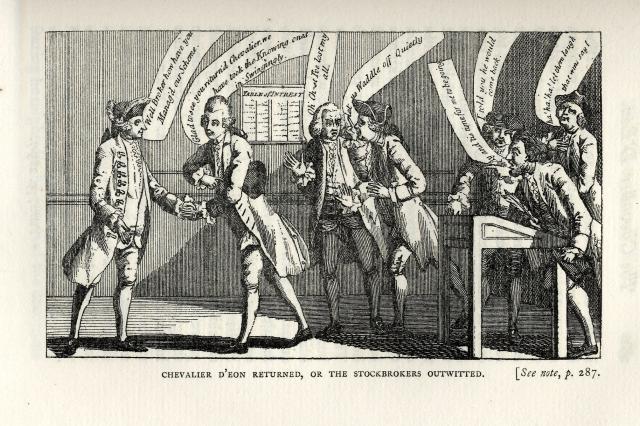

It was during their time in London, in the late 1760’s, when rumours began to circulate that the Chevalier was a woman. No one knows who started the rumours, although it has been suggested that they may have come directly from D’Eon. London society was gripped and soon bets or policies of insurance were being taken out on the issue. It’s estimated that at the height of the betting, policies worth £120,000 were tied up in the question of the Chevalier’s gender.

D’Eon not impressed by speculation and on the death of Louis XV in 1773, began negotiating their return to France. In 1775, the Chevalier signed a Transaction allowing them to return, on the condition that they returned documents relating to the Secret du Roi still in their possession. In response, D’Eon, having claimed to have been assigned female at birth, demanded that the French government recognised them as such. King Louis XVI complied, but required that they wore women’s clothing. D’Eon did this, rebelling slightly by continuing to wear their Order of St. Louis. In 1777 D'Eon returned to France and was invited by Marie-Antoinette to employ the services of the royal dressmaker.

In 1785 they left France for London again, giving fencing demonstrations and they were given a pistol by the Prince Regent for winning a match with the Chevalier de Saint-George in 1787. In 1789, the French Revolution put an end to D’Eon’s pension and they gradually slipped into poverty and died in 1810. But that’s not the end of the story. There’s one more one chapter of the Chevaliers’ life that still deserves a mention.

Freemasonry

Whilst in London, D’Eon had become a freemason, joining the Lodge of Immortality No. 376, which met at the Crown and Anchor in the Strand, in 1768. The Lodge had been established by a French exile called de Vignoles in 1766 for European Masons in London. De Vignoles had been employed as D’Eon’s Private Secretary since 1765 and in 1770 an internal feud broke out in the lodge between French and German speakers. A year later de Vignoles and the French faction, including D'Eon petitioned the Grand Master for help. The lodge does not appear to have lasted much longer than the year of the petition and the Chevaliers' involvement with Freemasonry ended there too.

Once society considered the Chevalier a woman, it would have been impossible for them to attend a lodge meeting, despite many masonic friends, including Wilkes and Ferres. It did not stop cartoonists and artists referring to D’Eon’s Freemasonry. The Chevalier’s favourite portrait of themselves shows them wearing female clothes, a sword, the Cross of St. Louis and a Masonic apron and it is titled, The discovery of a female Free-Mason.

You can see the portrait on display as part of our Familiar Faces exhibition in the museum corridor. A print of the fencing match with the Chevalier de Saint-Georges also features in our Treasures exhibition, on in the Library until the end of 2021.